Ed Rutherford here. Mary Rose opens this weekend, and I wanted to give those of you who are interested a glimpse into parts of the process of adapting the original public domain J.M. Barrie play into this world premiere musical. One of the things I was interested in exploring in the adaptation was to have an answer (even if it’s one that is only kept to myself and the cast and creative team) for exactly what happens to the title character when she vanishes on the Island and then is returned unchanged a long time later, with only the vaguest impressions of where she’s been and no knowledge of how long she’s been away. I was also interested in exploring how Mary Rose herself might feel about or try to understand what has happened to her. For the adaptation, my way into this was to think about another author whose stories really got under my skin as a child: Hans Christian Andersen.

You know his stories, even if you don’t necessarily realize that he was the source of them. Like the Brothers Grimm, he has been often adapted and updated in other media, frequently in ways that bowdlerize the darkness of the source material. He’s responsible for The Little Mermaid (the version where, spoilers, the mermaid dies), The Snow Queen (which many years later was the seed that sprouted into Disney’s ‘Frozen’ franchise), The Ugly Duckling, Thumbelina, and a host of other stories that still permeate our collective consciousness.

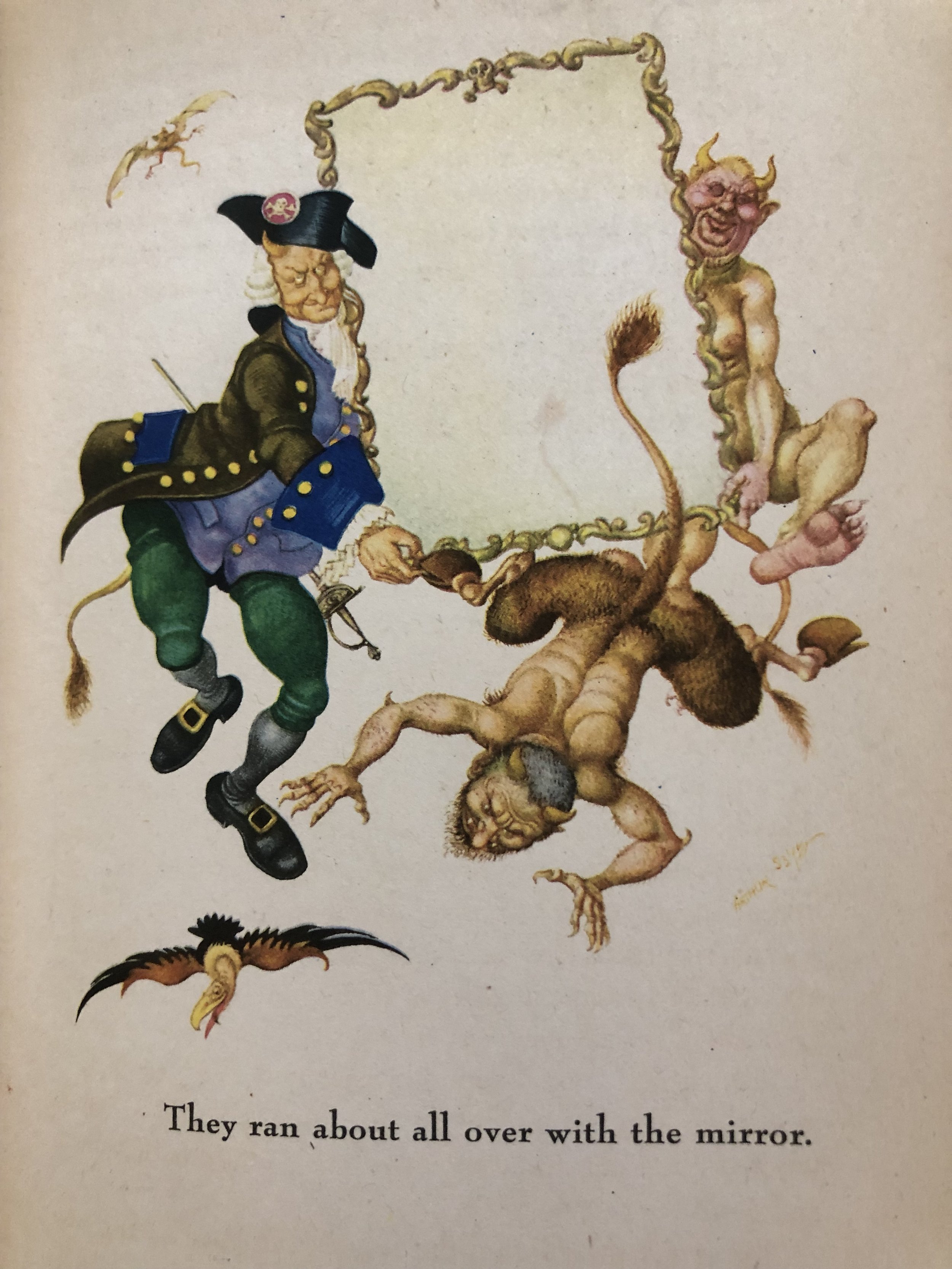

The hard copy collection of those fairy stories that I grew up on was the 1940’s ‘Andersen’s Fairy Tales’ with illustrations by Arthur Szyk, and that copy (although increasingly battered and worn) still sits on my bookshelf to this day. The illustrations are vivid and intense, and have an intensely stylized quality to them that so often characterizes Szyk’s work. His drawings often resemble stained glass windows to me, with impassive faces of angels and cherubs applied to especially his drawings of children. Some of his more detailed work even smacks of illuminated medieval manuscripts. Other drawings have the flavor of a political cartoon in their exaggeration and indeed Szyk was a political cartoonist as well as an illustrator. Here’s an example of a moment Szyk portrays from the beginning of The Snow Queen:

The above is from the very beginning of The Snow Queen, before we are introduced to the title character or the two children Gerda and Kay. The opening of the story explains about a magic mirror that twists everything that appears in it to magnify the worst qualities of it, and as a prologue to the main tale describes the wickedness that follows when the mirror shatters and its shards are flung across the earth.

Another character that oddly appears at least by mention in two different Andersen stories is the Marsh King. He is some sort of fey creature that rules over the bogs and swamps of the world, and woe befall any who sink into his domain. Here he is in one of Szyk’s drawings:

The first of Andersen’s stories that mention this character is “The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf.” Much like many of the stories in Shockheaded Peter, the tale involves a child being punished egregiously for doing something improper or ‘wicked.’ In this case the child is charged with bringing her mother a loaf of bread, and is so preoccupied with keeping her outfit and fine shoes clean that during the trip she drops the loaf in a swamp and steps on it to cross over a puddle. Instead, she sinks into the Marsh King’s den and all manner of unpleasant things happen to her. Szyk finds this story so compelling that he’s drawn it not once but twice: first immediately after her descent, and second when she becomes a kind of curio or ornament on display in the Marsh King’s world, frozen still alongside other sinners:

But the Marsh King is also a key figure in another Andersen story, titled appropriately enough “The Marsh King’s Daughter.” It is sprawling tale involving Vikings, storks, Egypt and transformations into toads among other things, but one part struck me as very significant and similar to Mary Rose’s situation. Near the end of the story, the title character finds herself in similar situation to Mary Rose: she, too, vanishes and returns after what seems to her to have been the briefest of moments, but to the rest of the world a longer time has passed. It’s an odd twist to the end of the tale, that arguably snatches away what otherwise would be a standard “prince and princess marry and live happily ever after” faerie tale ending.

One of my conceits for this adaptation of Mary Rose is that, since Hans Christian Andersen was first translated into English and available to the British public by the mid 1800s (i.e. by the time the character of Mary Rose would have been a young child), the character knows these stories, grew up on them, and in one key song late in the show tries to explain to herself what has transpired in terms of these tales. The name of the song? “The Marsh King’s Daughter.”

Hope you’ve enjoyed this little detour into the adaptive process, and that you’ll check out Mary Rose! Tickets are on sale and we start performances any day now!